The variable area flowmeter is a reverse differential pressure meter used to accurately measure the flow rate of liquids and gases. The flow meter generally comprises a vertical, tapered glass tube and a weighted float whose diameter is approximately the same as the tube base.

How the Variable Area Flow Meter Works

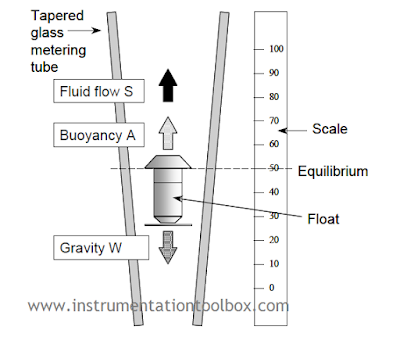

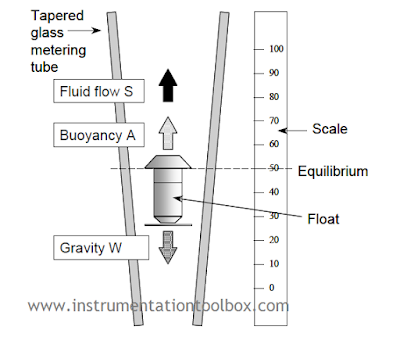

The schematic below shows the basic design of a variable area flow meter:

|

| Basic Design of a Variable Area Flow Meter : Photo Credit Brooks Instrument |

During operation, the fluid or gas flows through the inverted conical tube from the bottom to the top, carrying the float upwards as indicated by the arrow in our schematic above. Since the diameter of the tube increases in the upward direction, the float rises to a point where the upward force on the float created by differential pressure across the annular gap, between the float and the tube, equals the weight of the float.

As shown in the schematic above, three forces are seen acting on the float:

(a) A constant gravitational force, W.

(b) A buoyancy force, A, which is constant if the fluid density is constant (According to Archimedes principle)

(c) Flow resistance force S, the upward force of the fluid flowing past the float.

Two of these forces are acting in an upward direction as indicated by the arrows in the schematic above. They are the buoyancy force A and the flow resistance force S. The gravitational force W, acts downward.

When the float is stationary, W and A are constant and S must also be constant. In a position of equilibrium (floating state) the sum of forces S + A is opposite and equal to W and the float position corresponds to a flow rate that can be read off a scale.

A major advantage of the variable area flowmeter is that the flow rate is directly proportional to the orifice area that, in turn, can be made to be linearly proportional to the vertical displacement of the float. Thus, unlike most differential pressure systems, it is unnecessary to carry out square root extraction.

Flow Rate Equation for the Variable Area Flow Meter

In a typical variable area flow meter, the flow Q can be shown to be approximately given by:

$Q = CA\sqrt{ρ}$

where:

Q = flow

C = constant that depends mainly on the float

A = cross-sectional area available for fluid flow past the float

ρ = density of the fluid

As shown by the flow equation above, indicated flow depends on the density of the fluid which, in the case of gases, varies strongly with the temperature, pressure and composition of the gas.

Floats Used in Variable Area Flow Meters

A wide variety of float shapes are available for use in variable area flow meters. The weight, shape and materials of these floats are adapted to the individual installations. The common floats used are:

A. Ball float

B. Viscosity-immune float

C. Viscosity-dependent float

D. Float for low pressure drop

|

| Different Shapes of Floats used for Variable Area Flow Meters. Photo Credit: ABB Flow |

The ball float (A) is mainly used as a metering element for small flowmeters. The viscosity-immune float (B) is used in applications where viscosity change is a critical factor. The viscosity-dependent (C) float is used in larger sized variable area flowmeters. Floats for low pressure drop (D) applications are very light in weight with relatively low pressure drops. Its design requires minimum upstream pressures and is usually preferred for gas flow measurement.

Flow Metering Tubes

The meter tube of a variable area meter is normally manufactured from borosilicate glass that is suitable for metering process medium temperatures up to 200 °C and pressures up to about 2 - 3 MPa. Because the glass tube is vulnerable to damage from thermal shocks and pressure hammering, it is often necessary to provide a protective shield around the tube.

Variable area meters are inherently self-cleaning since the fluid flow between the tube wall and the float provides a scouring action that discourages the build-up of foreign matter. Nonetheless, if the fluid is dirty, the tube can become coated – affecting calibration and preventing the scale from being read. This effect can be minimised through the use of an inline filter.

The temperature and pressure range may be considerably extended (for example up to 400 °C and 70 MPa) through the use of a stainless steel metering tube. Again, the float can incorporate a built-in permanent magnet that is coupled to an external field sensor that provides a flow reading on a meter.

Floats Centering Methods in Variable Area Meters

An important requirement for accurate metering is that the float is exactly centered in the metering tube. One of three methods is usually used:

(a) Slots in the float head cause the float to rotate and center itself and prevent it sticking to the walls of the tube. Slots cannot be applied to all float shapes and, further, can cause the indicated flow to become slightly viscosity dependent.

(b) Three molded ribs within the metering tube cone, parallel to the tube axis, guide the float and keep it centered. This principle allows a variety of float shapes to be used and the metering edge remains visible even when metering opaque fluids.

(c) A fixed center guide rod within the metering tube is used to guide the float and keep it centered. The use of guide rods is confined mainly to applications where the fluid stream is subject to pulsations likely to cause the float to ‘chatter’ and possibly, in extreme cases, break the tube. It is also used extensively in metal metering tubes.

|

| Floats Centering Methods in Variable Area Flow Meter Design |

Materials Used in Construction of Floats

The float material is largely determined by the medium and the flow range and includes: stainless steel, titanium, aluminium, black glass, synthetic sapphire, polypropylene, Teflon, PVC, hard rubber, Monel, nickel and Hastelloy C.

Advantages of Using a Variable Area Flow Meter

1. It has wide range of applications.

2. It has a linear float response to flow rate change.

3. It has a 10 to 1 flow range or tum-down rate.

4. Easy sizing or conversion from one particular service to another.

5. Ease of installation and maintenance.

6. Simplicity and low cost.

7. High low-flow accuracy (down to 5 cm3/ min).

8. Easy visualisation of flow

Disadvantages of Using a Variable Area Flow Meter

1. It has limited accuracy.

2. It is susceptibility to changes in temperature, density and viscosity.

3. Fluid medium must be clean, no solids content.

4. Erosion of device (wear and tear).

5. It can be expensive for large diameters application.

6. It operates in vertical position only.

7. It requires accessories for data transmission.